Pantheon Design alleviates supply chain uncertainty with factory-grade 3D printing • ZebethMedia

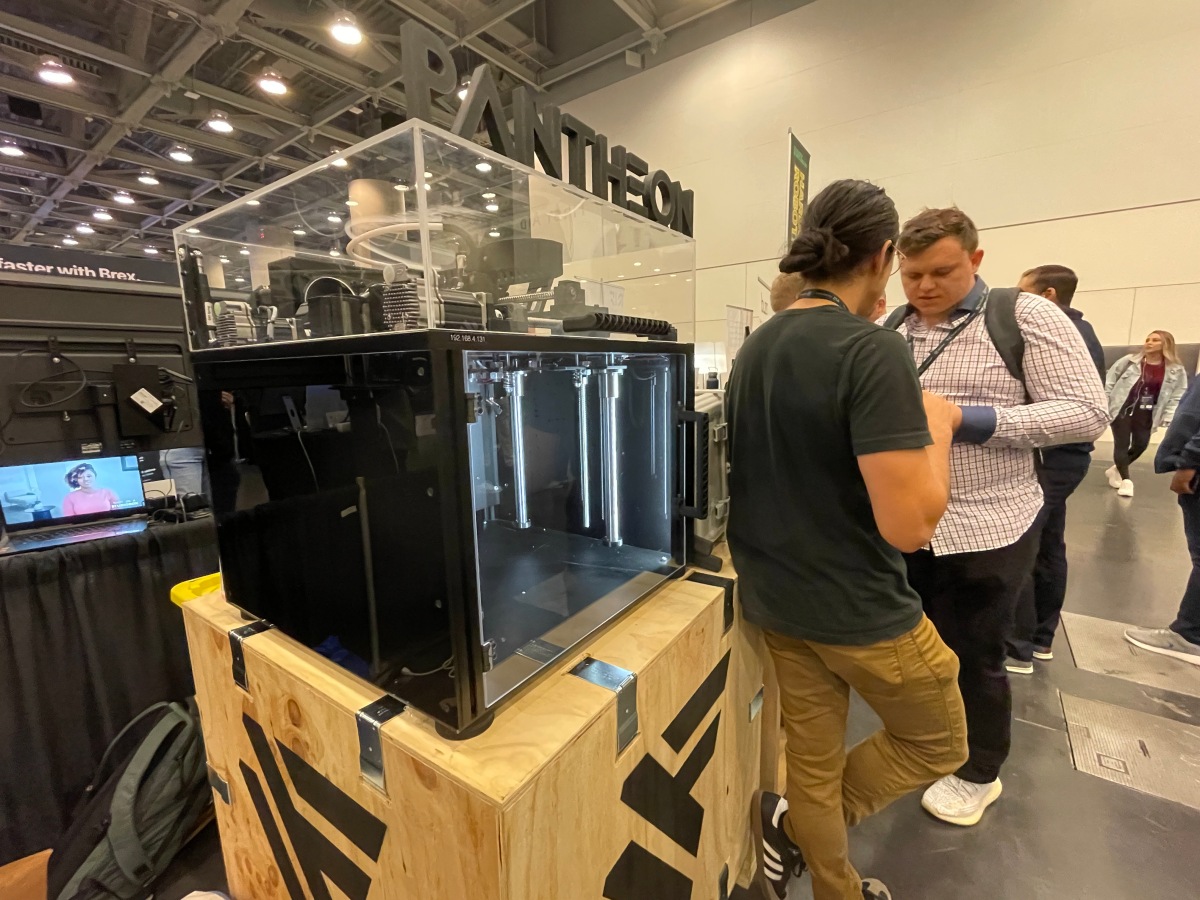

In the midst of the pandemic, Pantheon Design, a maker of industrial 3D printers from Vancouver, BC, suddenly found itself getting orders from factories in the Midwest, the center of heavy industries. The reason? These manufacturers were having a hard time getting parts out of China as COVID-19 restrictions in the country squeezed global supply chains. One of Pantheon Design’s e-mobility customers waited 18 months before its injection molds, which are used for producing parts, arrived from China. If your electric vehicle or home appliance order is taking longer to arrive, chances are port closures and lockdowns in the factory of the world are messing up your supplier’s production timeline. For a long time, 3D printers were too expensive, slow, and short-lived to be economically viable for manufacturers, observes Bob Cao, co-founder and CEO of Pantheon Design, as he speaks to ZebethMedia as one of the Disrupt Startup Battlefield 200 companies. Many of the 3D printing startups that secure big VC checks are run by smart people who have never been in a real factory, which is hot and smelly, says the entrepreneur. “So their machines break down all the time.” “They make the product for prototyping, but they try to sell the idea for manufacturing,” he adds. Cao’s founder story follows a familiar pattern seen among engineers: five years ago, he and his co-founders bought a bunch of 3D printers to build products for industrial customers, but the third-party devices weren’t meeting their expectations, so they set out to build their own. Parts created by Pantheon’s 3d printer. The result is the HS3 3D printer, which is a sleek-looking cube measuring 300mm on each side and weighing 46.7 kilograms, featuring black anodized aluminum, which has been treated to achieve a durable finish. The device is able to print carbon fiber parts that are as sturdy as metal and 5-10 times faster than other options on the market thanks to the startup’s patented methods, according to Cao. Moreover, it’s able to do it at a competitive cost even in comparison to Chinese suppliers. The startup has sold 40 HS3 units — all assembled in-house in Vancouver with parts manufactured in Canada — since starting shipping the machine nine months ago. Each printer costs $15,000, but the bigger chunk of the company’s revenues comes from selling filaments. Also called the “ink” for 3D printers, filaments range from $50-150 a kilo, which brings a nice 90% profit margin, and most of the company’s customers spend about $500-800 a month on them. Pantheon Design has raised $800,000 in funding from a mix of investors in Canada and the U.S., including the Boston-based accelerator Techstars. The company is also buoyed by revenues it generated from its previous business of printing products and prototypes for clients, and two of its proudest moments include printing entire concept motorcycles for Honda and all the sci-fi props in the Netflix film The Adam Project.